Awake at Midnight welcomes Vivian Vande Velde, author of many children’s and young adult books that deal with magic, curses, witches, and ghosts. She won the Edgar Award for Never Trust a Dead Man, and has appeared on the American Library Association’s list of Best Fiction for Young Adults numerous times, for selections such as Being Dead and Companions of the Night.

Your horror tends to lean towards fantasy, and even your high-fantasy novels have a taste of horror in them. What is your favorite genre to write in? Do you have a favorite to read?

Your first question has already thrown me off, Sean, because I don’t consider myself a horror writer. Even when I’m writing a ghost story with a malevolent ghost, I don’t think of it as a horror story. I guess it’s a matter of degree. In most cases, I think that readers are not seriously worried about the fate in store for the majority of my characters. The book I’ve written that I consider to be the darkest —and therefore closest to horror— is All Hallow’s Eve.

Primarily I consider myself a fantasy author. It’s just that my fantasies veer all over the fantasy board—including talking animals, fairy tales (both fracturing existing fairy tales and writing original stories that use themes and characters from fairy tales, such as princesses, witches, enchantments), also ghost stories, vampire stories, stories involving magical abilities, and some that could almost be considered science fiction (involving time travel, genetic engineering, or set slightly in the future where we can assume a technology one step beyond virtual reality)—but “almost science fiction” because there’s no serious attempt to make the science convincing.

Mostly I read middle-grade and young adult novels in an attempt to keep current with all the writers I know. I like science fiction, fantasy, mystery, stories not set here and now (though I read some of those, too; they’re just not usually my first choice). The last book for young people I read was Julie Berry’s All the Truth That’s in Me, and the last adult book was the story of Louis Zamperini’s World War II ordeal, told by Laura Hillenbrand in Unbroken.

What are some of your favorite horror movies?

Truthfully, I am too much of a coward to watch horror movies. When I was about 12, I talked my mother into letting me stay up to watch Bela Lugosi in Dracula on the late show. Couldn’t sleep well for weeks for fear that Dracula was scaling the outside of our house to peek into my bedroom window. Demanded of my mom: “What were you thinking, letting me watch that?”

Of course, that didn’t keep me from watching every other vampire, werewolf, monster, or Frankenstein-inspired movie that was on TV in the 60’s.

These days, I think there’s more than enough horror on the evening news.

You based There’s a Dead Person Following my Sister Around on the Underground Railroad and the Erie Canal, and “For Love of Him” in the Being Dead collection was set in Mt. Hope Cemetery in Rochester, NY. Do you find that historic landmarks give you stronger inspiration or do you explore them purposely given their educational value?

Both. There’s something very evocative about writing about a real place. (Dangerous, too, for a writer can sometimes mistakenly believe that her words are creating the same picture and atmosphere in her readers’ minds, when it’s only the writer’s memory at work in her own brain.)

It’s also fun to set a story in a specific place where readers from that area can recognize the geography.

But I was certainly aware while writing There’s a Dead Person Following My Sister Around (whose characters —those who are alive— live in the Rochester area in the present day), as well as A Coming Evil (fictional French town in 1940), and the short story “The Witch’s Son” (set in a made-up New York state village in 1776) that there are fewer kids who say, “I want to read a story about the Underground Railroad, or about Jewish and gypsy children hiding out during World War II, or about the Revolutionary War” than there are kids who can be enticed into reading such stories with the promise of ghosts.

On your website, you mention that you often find inspiration in old photographs; tell me about your own collection.

I’m sometimes asked to lead writing workshops for students—and I’m usually given about 45 minutes to an hour to do it. We need to work quickly, and I’ve found that one shortcut is to provide pictures of potential characters, about whom I’ll ask questions, such as: What do you think this person might be afraid of? Tell me a secret about him—is there something he doesn’t want anybody else to know? Can you think of something about the person that he himself might not be aware of?

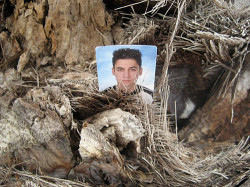

I don’t want to use pictures of anybody the young writers are likely to know—such as actors, who have their own stories associated with them, both in the tabloids and in the roles they’ve played—and I don’t want to have the writers making up stories about my relatives. I discovered www.timetales.com which has pictures people have found, perhaps in a photo album forgotten or abandoned when someone moved out of a house, or left behind as a bookmark in a returned library book, or as trash blowing across someone’s lawn. I’ve also bought pictures at flea markets or antique stores.

These are not pictures of oddities such as Ransom Riggs has used in his book Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children. These are simply people who have what I consider to be interesting faces. I try to include a wide variety of types of people (varying in age from toddlers to grandparents, male and female, people who look of different ethnic types, posed formal portraits from the dawn of the photographic age and informal snapshots that someone could have taken earlier today) so that workshop participants can select a subject who interests them.

www.timetales.com started in the Netherlands, and many of the pictures from that site were found in Europe. I look at the happy family groupings that seem to date from the 1940’s, and know the people in them could have had no idea how their lives were about to be disrupted by World War II. Did some of these pictures end up lost because the families fled from their homes–or because they didn’t flee in time to avoid Nazi concentration camps and gas chambers?

How can a writer not be intrigued: Who is this woman standing in the boat?

What’s going on with these two men and the young woman holding the rifle?

Why was a picture of this young man placed at the foot of a tree?

A number of your stories, including User Unfriendly and the recent Deadly Pink, draw on modern technology. As an author, how do you approach the difficulty in keeping a story that involves computers from becoming dated?

Vagueness is the best defense. In the short story “Curses, Inc.” I went into way too much detail, so that readers can tell my character is definitely using a dial-up modem, which is unfortunate because the story didn’t need that. And, of course, many of my stories otherwise set in current times are a bit dated because the characters don’t have cell phones.

Technology is such an ingrained part of everyday life, do you think it can be omitted from a modern day story in which it does not play a central role or is it now impossible to ignore?

You can’t ignore the pervasiveness of cell phones and the ability they give us to both contact others and to take pictures. There’s also access to the internet, DNA testing, tracking people through the GPS in their phones—all of which prevent certain plot twists that were perfectly fine just a short while ago (all right, all right: within my lifetime, without my having to be specific about exactly how old I am!).

On the other hand, this does not impact books already written. Readers can fall in love with Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles even though we have known for a good long time that there was never a civilization on Mars.

What goes into creating characters we can empathize with but who will also knowingly be placed in a situation drenched with horror?

This is a problem for all authors, no matter what genre. Story is about conflict and overcoming obstacles. Say I’ve written a story about a beautiful princess who is kind and healthy and happy, and she has a loving family and lots of friends, and she lives in a just and prosperous kingdom that is at peace with all its neighbors, and she has a brave and handsome suitor she loves and of whom everyone approves… Have I put you to sleep yet? I’m putting myself to sleep. We might envy that princess’s blissful life—but we don’t want to read about her. We want one or both of her parents to die so that she’s on her own; we want her to be accused of something she didn’t do and be exiled, imprisoned, or sentenced to death; we want an infestation of wicked witches, dragons, or sea monsters to threaten her home; we want her to be betrothed to a beast. And the funny thing is that the more we like her and the more we’re squirming to see

her in such an awful situation– the better we’ll like

her story.

As far as an author killing off characters, if we’ve made the characters unlikable so that the reader won’t feel bad at his death, what’s the point? This happens a lot in TV mysteries as well as in teen slasher movies: The victim has been unpleasant and abusive to all the people around him—which makes for many suspects, but also leaves the impression that only mean, ugly people get killed.

Books for younger readers are based much more in the imagination than the average best-seller. Do you feel there is a level of intensity that is too frightening for certain age groups? How do you judge that boundary in your own writing?

You’ve asked yet another question without an easy answer. I was once a judge for a writing contest for kids in grades 1 – 8 that was sponsored by a local book store. Because the contest happened to take place in October, quite a few of the kids were in a Halloween frame of mind and many of them (well, not so much the 1st and 2nd graders, but definitely the 4th, 5th, and 6th graders) wrote spooky stories. Some of them included gruesome details no author would ever put into books for kids that age to read, including at least one decapitated mother whose headless corpse then comes after her kid. Were the kids who wrote those stories little ghouls? Well, maybe. But the thing is that since they’d written those stories themselves, the stories had little power—the kids knew they were made up. A book written and published by an adult and found in a book store or library would seem much more real and permanent and therefore disturbing.

As for what is appropriate for what age, there is no single answer, which is why one parent will read with her child a book that another parent decides is off-limits for hers.

(A good clue to how intense a book might be is for a concerned parent or librarian to note the age of the main character. Too many parents say, “Oh, my child is an excellent reader,” and let that child read books meant for older readers—then complain about the content.)

Do you think authors and editors can be counted on to “self-regulate,” or should there be some form of oversight? What would you think of a ratings system for books?

I am in general opposed to letting other people (especially a committee) do my thinking for me. Every single book in the world has something in it that someone would find objectionable. (“This story has a family celebrating by eating pizza and cookies and ice cream. The eating of junk food to satisfy emotional needs can lead to a lifetime of food abuse, and this book encourages that.” Or: “This is a story about a kid who wants a dog, and at first his parents say no, but then they give in. Some families absolutely can’t have pets because of allergies or restrictions in their lease. Don’t you realize this book makes those kids feel their parents don’t truly love them?” Or: “In this book, the kid tries very hard and succeeds. That doesn’t always happen, you know. You’re making my kid feel like a loser.”)

Authors need to write stories that feel true to them. Editors can be counted on to try to make the story accessible to the biggest number of readers so that more copies can be sold. (Book publishing is a business.) It’s up to individual parents to decide whether a particular book is right of their own kids. I am very much in favor of parents reading some of their kids’ books with them. And discussing. (“Wow, did that ending take you completely by surprise?” Or: “I wonder what I would have done in that situation, given that I don’t have convenient superpowers…” Or: “Do you think there’s such a thing as a gene that makes someone evil?”)

What’s in the works? Do you have any irons in the fire that we can look forward to seeing soon?

I don’t know how soon you can look forward to seeing it, but the last project that I just sent off to my agent is a novel tentatively called Mouse Brother. It’s about two brothers, princes, 12-year-old Aldrys and 13-year-old Kelan, who encounter a witch who turns Kelan into a mouse. Eventually the spell is reversed, but by then Kelan has spent so long as a mouse that he has difficulty readjusting to being human– and it is Aldrys who needs to take on the role of protector and caregiver. Can Aldrys bring his brother back before their father, the king, disowns him? And before the princess to whom he is to be betrothed to seal a political alliance catches on and calls off both the betrothal and the alliance?

Related Posts: Curses, Inc.