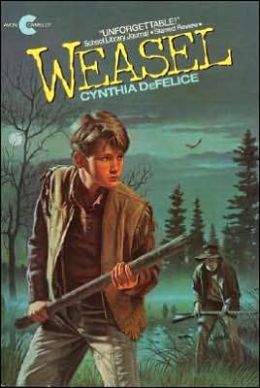

Weasel

by Cynthia DeFelice

HarperCollins, 1991

128 Pages

Middle-Grade (9-12)

![]()

![]()

Although this book clocks in at barely over a hundred pages, it is one of the most memorable books I have ever read. It picks up like a freight train and won’t let go until you reach the end of the line.

It begins on a dark night when a bizarre looking man shows up at the door of two children on the American frontier. Their Dad has not returned home from a hunting trip for a day or two, which was odd. Their mother was lost to fever, so they were utterly alone when the stranger cam knocking. The man beckons them to follow him into the forest. Why would they do such a crazy thing? Because he shows them their mother’s locket that was always carried by their father. Did he give it to the weird white man in Native American dress and a top hat so the kids would know it was safe to follow, or is it a trap?

This book touches on the true violence that existed on both the lawless frontier and in life, but it is revealed in such a way as to make the reader think. Long after the story is done, we wonder about the cost and lure of revenge, about pain and loss, and about the motivation behind hateful deeds. It is suitable for a mid-grade audience, and will thrill young men who hate to invest their time in a longer novel.

Nathan and Molly’s father is in the man’s cabin with an infection and a fever from being snared in a bear trap. They do their best to heal him, but there is still danger lurking nearby in the form of a man called Weasel. The story goes that Weasel was once a government agent sent to clear the land of Shawnee Indians, but that he went bad. Once the Indian population had been relocated to Kansas, he stayed on, a sociopath, killing anyone he could for the sake of murder.

Weasel shoots and kills a pig, and Nathan discovers its body. Nathan spends the day burying the pig, because “civilized men bury their dead.” |

Nathan wants revenge, but how can he stand up to a madman like Weasel? Even if he could get the dangerous and evil man in the sights of his father’s rifle, would he have the courage to shoot a man down? As if the trap his father was caught in weren’t enough harm to inflict upon one family, Weasel goes to their homestead and steals their horse and mule and kills a sickly pig, leaving its carcass to rot. Nathan is heartbroken.

The white man who lives in a wig-e-wah like the local native people once did is named Ezra, and he has his own painful tale about an encounter with Weasel. Ezra helps nurse their father back to health along with the herbal healing Molly learned from her mother, but when the family returns to their home, Nathan feels Weasel’s presence close by in the wild, waiting to do them further harm. What can he do but go and face the threat?

There are a few chapters at the end of the book after the train ride comes to a halt, purposefully exploring how life goes on after the encounter with Weasel. They are important chapters, and allay what might be a disappointment for those expecting a Rambo-style fight scene.

And even if Weasel’s not around, there’s likely to be someone else like him, or some other kind of meanness and sorrow and sadness. But there’s plowing and planting, and kinfolk and Kansas, and whistling and fiddling, too. That’s what Ezra wanted to tell me,I think. And I reckon if he can let go of hating Weasel, I can, too.